Photograph: Rudolph Faircloth, Illustration: Brian Grey, USA TODAY Community

Because the Nationwide Museum of African American Music opens its doorways, journalists from the USA TODAY Community discover the tales, locations and individuals who helped make music what it’s at the moment in our expansive collection, Hallowed Sound.

Fifteen-year-old Bobby Rush wanted a match.

With a pinch of soot from the rubble of a flame, Rush scribbled a mustache above his lip. He pulled his hat low and slunk into Drums, a gravel street joint with cracks within the ceiling that, on a superb night time, squeezed in a number of dozen individuals.

A child in 1940s Pine Bluff, Arkansas, Rush knew he should not be sneaking into backwoods golf equipment. However he could not assist it.

The music was too good.

On stage, at Drums or the “Huge Rec” auditorium on the town, Rush watched the good blues shouter Huge Joe Turner and searing metal guitarist Elmore James — artists who formed a region-defining sound for many years to return.

As a younger Black artist within the segregated South, he noticed musicians who wielded blazing, unequalled ardour.

Shunned from white theaters, Black musicians within the Jim Crow South entertained on the so-called “Chitlin’ Circuit,” a community of golf equipment and theaters in African-American neighborhoods that hosted a number of the greatest expertise in American music historical past.

“The juke joint, man, that is all there was,” stated Rush, a Grammy Award-winning Mississippi troubadour who’s been working crowds because the 1950s. “I did not know something about what they name ‘upscale’ place … I did not know something about nothin’ however juke joints. I believed that was it.”

Artists on the Circuit — a centerpiece of the Black music trade throughout a long time of segregation — honed efficiency abilities and sounds that proceed to affect music at the moment.

In cities the place Black musicians forcibly had been advised the place they might and couldn’t play, Billie Vacation, Rely Basie, Muddy Waters, Ray Charles, B.B. King, Marvin Gaye and numerous others perfected songs that stand at the moment among the many most necessary contributions to the American musical canon.

The Circuit was named after Chitterlings, a dish ready from hog intestines some view as second-class. But there was nothing second-class in regards to the music made in these rooms.

“It is these nightclubs the place the music occurred,” stated Dr. Steven Lewis, curator on the Nationwide Museum of African American Music. “You actually haven’t got the story of so many of those musicians with out understanding the African-American leisure world that was grounded within the Black neighborhood. That is the place so lots of the artists that we rejoice in the museum bought their begin.

“It is an important a part of the story.”

Roots of the Chitlin’ Circuit will be traced as deep as Vaudevillian leisure in early 20th century African-American communities. These artisans — dancers, comedians and musicians — carried out in golf equipment as far west as Oklahoma, stretching via the South and far of the East Coast.

These exhibits had been booked by Theater House owners Reserving Affiliation, or TOBA, a community of theater house owners catering leisure in Black communities.

TOBA launched within the 1920s and Milton Starr, a white Nashville businessman who owned the Bijou Theater, served as its president. These venues usually hosted artists featured on race data — a advertising and marketing tactic deployed in early years of the file enterprise to segregate Black and white listeners.

“TOBA acts, they might’ve been virtually like a minstrel present,” stated Preston Lauterbach, creator of “Chiltin Circuit and the Street To Rock ‘n’ Roll,” a definitive e book on the Circuit. “There would’ve been numerous totally different acts. It was a spread present.”

Photograph: ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORY, Illustration: Andrea Brunty, USA TODAY Community

Inventive circles on the time, nevertheless, referred to the group by a totally different identify: Powerful On Black Artists.

Situations for entertainers had been usually disagreeable and demeaning, Lewis stated.

The TOBA did not face up to the Nice Despair. It folded as leisure circles reeled from the years of monetary hardship that started the 1930s.

However the music survived.

Black owned, operated and patronized venues welcomed Black artists all through the South, opening doorways to a full of life arts neighborhood cultivated in an period outlined by Jim Crow segregation.

Some had been juke joints with filth flooring, others had been nightclubs that weathered the Despair.

Some artists performed in barns, some stuffed dance halls and some ripped 4 gigs a night time at polished theaters able to overflow with a toe-tapping escapism that washed away hardships that waited simply outdoors the door.

Many of those halls would ultimately shutter. However some, such because the Apollo Theater in New York Metropolis, Royal Peacock in Atlanta or the Dreamland Ballroom in Little Rock, nonetheless stand at the moment — brick-and-mortar vestiges of the artwork created a long time earlier.

On this 1955 file picture, trumpeter Clark Terry walks together with his son Rudolph below the Apollo Theater marquee after Terry’s first stage present with Duke Ellington’s band within the Harlem neighborhood of New York Metropolis. In 2018, individuals gathered at a makeshift memorial for singer Aretha Franklin outdoors the Apollo Theater.

LEFT: On this 1955 file picture, trumpeter Clark Terry walks together with his son Rudolph below the Apollo Theater marquee after Terry’s first stage present with Duke Ellington’s band within the Harlem neighborhood of New York Metropolis. RIGHT: In 2018, individuals gathered at a makeshift memorial for singer Aretha Franklin outdoors the Apollo Theater.

G. Marshall Wilson/AP; Frank Franklin II/AP

Tickets on the Circuit typically value a $1 or $2, and drinks had been cheaper. Pay for the entertainers? That relies on how hungry they had been, Rush stated.

“Generally you play for the chitlins, that is what you’d get,” stated Rush, the self-described “king” of the Chitlin’ Circuit. “We performed so nicely in Argo, Illinois, not Chicago, a suburb of Chicago, the man [gave] us two plates of chitlins and 4 hamburgers. We ate one chitlins, we promote the opposite for $.35 and we promote the hamburgers for $.25. I would make a $1.25 or a $1.35 on my hamburgers each night time.”

In most neighborhoods, the venues had been located on “the stroll,” a busting strip the place one may discover markets, BBQ pit stops and beer joints lining the street. Most segregated cities had a stroll — Jefferson Avenue in Nashville, Candy Auburn in Atlanta, Rampart in New Orleans and, arguably one of the best identified at the moment, Beale Avenue in Memphis.

These blocks had been usually monopolized by a neighborhood entrepreneur who dabbled in actual property, playing, liquor and leisure. Lauterbach referred to those metropolitan “kingpins” because the “true spine of the Chitlin’ Circuit.”

Hallowed Sound: How Black artists influenced American music

Video contributors: Mike Fant, Eric Shelton, Max Gersh, Mandi Wright, Dinah Rogers, Mike Baker, Christian Monterrosa

And if membership house owners supplied a spine, then the music was the pulsing heartbeat.

“It is important as a result of it is not solely a gathering place, it is also a place the place a area people is ready to plug into the nationwide African-American leisure world,” stated Lewis.

Individuals “would work their asses off all week,” stated Alan Leeds, a music trade veteran who minimize his tooth working for James Brown on the Circuit. Many who paid $1 to bop to the week’s red-hot single did so after logging tense hours in factories, fields or different jobs.

“When Saturday got here, you actually needed to alleviate the stress,” stated Leeds, who organized Brown excursions within the early 1970s. “Psychological stress as a lot as bodily stress, due to the 24-7 oppression of Jim Crow, which on the floor individuals adjusted to. There is a subliminal have an effect on to dwelling that manner that we’re solely now starting to essentially acknowledge.”

And a few who stuffed weekend dancefloors discovered their very own path to levels.

About 1958, at Currie’s Membership Tropicana in north Memphis, a teenage drummer named Howard Grimes joined the home band.

Grimes started his profession at age 12, drumming for Memphis soul singer Rufus Thomas. Beneath Thomas he’d get a first-hand view on the Flamingo Membership and Membership Helpful, marquee Memphis spots.

However first got here nights at Tropicana, a brick-front café on Memphis’ bustling Thomas Avenue — an uptown district within the 1950s identified for golf equipment, film theaters and native grub. By 1961, Tropicana hosted a younger Isaac Hayes three nights every week.

“Mr. Currie introduced all the prime acts in there,” stated Grimes. “I bought an opportunity to see Hank Ballard and the Midnighters there. I noticed Invoice Doggett Dogett there. I noticed Ramsey Lewis there.

“That impressed me. … however what impressed me extra was the those who obtained that sort of leisure,” Grimes continued. “They was workin’ individuals. All sorts of individuals. They labored and so they got here out on the weekends and so they had a grand time. Ain’t by no means seen nothin’ like that.”

His abilities honed, Grimes would graduate to session musician at Satellite tv for pc Information, the label precursor to soul powerhouse Stax Information. He’d play as one of many Hello Rhythm Part, a troupe of musicians who backed Stax artists. Grimes performed on data with Otis Clay, Willie Mitchell and Al Inexperienced.

In its heyday, groundbreaking artists together with Louis Jordan, Duke Ellington, Fat Domino, Ella Fitzgerald, Sam Cooke, Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding and lots of extra carried out on the Circuit.

Little Richard — as soon as an aspiring feminine impersonator identified as Princess Lavonne — perfected his flamboyant persona on Circuit levels. Earlier than he grew to become a poster youngster for 1960s rock stardom, Jimi Hendrix labored many nights on stage at Membership Del Morocco on Jefferson Avenue in Nashville.

Earlier than Hendrix or Little Richard got here Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the godmother of rock ‘n’ roll, who introduced her revolutionary gospel-and-blues cocktail to golf equipment within the 1930s and ’40s.

On a given night time, audiences may see a comic, unique dancer, native cowl group, a number of songs from female and male assist singers and an hour-or-so headlining set.

Touring teams usually carried out a number of instances an evening in a single metropolis — an eight p.m. and 11 p.m. present, for instance, with potential for a matinee on weekends if demand known as for it.

Artists who could not afford to pay a touring band relied on native musicians to know the tunes once they rolled into city.

In his 2011 memoir “Le Freak,” Nile Rodgers — progressive co-founder of disco-soul outfit Stylish — described the Circuit as “our equal of sophistication A baseball.”

Golf equipment diverse from tin-roof huts to flamboyant variations of the cantina in “Star Wars,” he wrote.

“You had an extended technique to go to get to the majors, nevertheless it was a mandatory step,” he wrote, per GQ, including: “If a patron known as out ‘Chocolate Buttermilk,’ ‘Pusher Man,’ and even ‘I Need You Again,’ the band had higher play it and play it nicely.”

On stage, audiences noticed artists who “offered themselves in a chic manner,” stated Jerry Williams Jr., a former Chitlin’ Circuit performer identified greatest by his stage identify, Swamp Dogg. Williams minimize his first file as a 12-year-old in 1954 below the moniker Little Jerry, then carved a reputation for himself as an eccentric soul singer within the 1970s.

“And for those who bought an opportunity to return stage or one thing, you’d see them again there stitching, puttin’ costumes collectively,” he continued. “After they got here out on stage, they introduced you one thing you’d by no means seen.”

It could be like seeing Prince, drenched in his purple-clad prime, stage a present in a neighborhood besieged by poverty, Swamp Dogg stated.

“However he would nonetheless be Prince, doin’ his factor. Dressed like a mom f—-r,” Swamp Dogg stated.

For a lot of, the Circuit supplied a full, albeit grueling work schedule.

James Brown as soon as performed 37 exhibits in 11 days, Leeds wrote in his 2017 e book, “There Was a Time: James Brown, The Chitlin’ Circuit, and Me.” Brown referred to gigs as “jobs,” usually touring 51 weeks a 12 months.

Alabama Division of Archives and Historical past, Illustration: Andrea Brunty, USA TODAY Community

“He represented everybody on that Circuit, simply out of the fundamental economics of it,” Leeds stated. “He by no means overpassed the actual fact he was doing this to make a dwelling. Sure, it was creative within the sense that you simply had been making nice music … however, financially, you had been nonetheless struggling to assist the system that you simply needed and wanted to your artwork.

“[You] had been by no means turning down a good provide.”

Rush echoed that sentiment. Usually wearing a boisterous outfit — a “flashy” and “loud” look, just like jazzman Cab Calloway, he’d hit a visitor spot down the road from his headlining set, enjoying for 20 or 30 minutes, earlier than returning to his personal crowd.

“It is how I survived, man,” Rush stated. “I am an entertainer. It ain’t about enjoying or singing or no matter. It is about entertaining.”

Segregation, prejudice and systemic racism — a cultural illness nonetheless haunting the South at the moment — made journey troublesome, typically harmful for Circuit artists.

Eating places and resorts in some cities? Neglect about it, Rush stated.

“You were not in a position to sit down in no diner nowhere, man,” Rush stated of touring within the deep South on the time. “Particularly a Black man enjoying the blues. You were not in a position to sleep in no resorts.”

In main cities, A-list artists may afford rooms in Black resorts, and most knew which neighborhoods alongside the Circuit would welcome a convoy of African-American vacationers on the time.

Black entertainers confronted totally different obstacles in small cities, stated Lewis.

“In a small Southern city the place there was an viewers and you may earn cash, you will have to endure some actually troublesome situations,” Lewis stated. “That was particularly laborious on the much less well-known teams, who had been much less prone to be a headliner at an enormous theater.”

Those that could not afford a room relied on the kindness of locals.

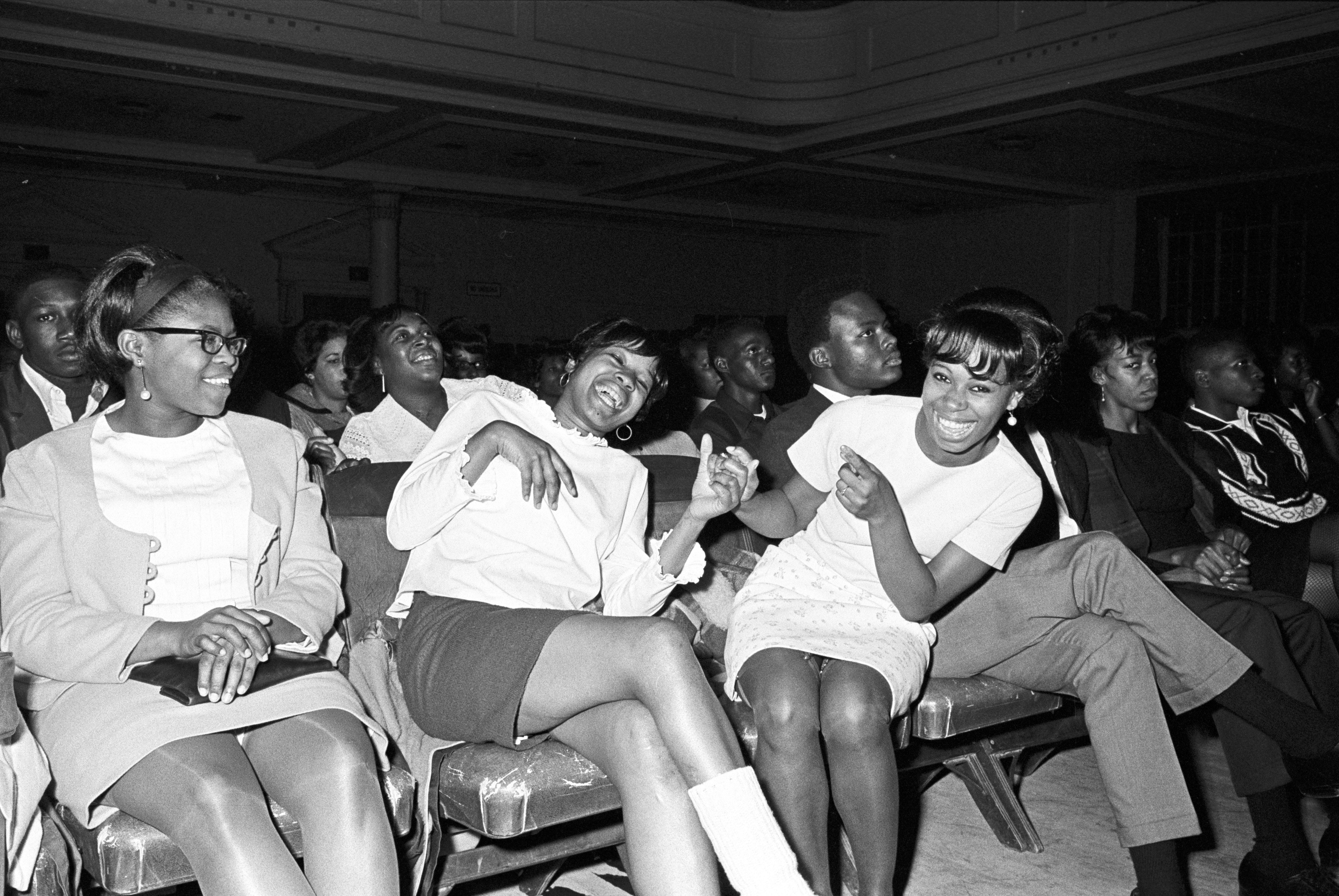

Younger ladies within the viewers throughout a efficiency of the Otis Redding Present on the Montgomery Metropolis Auditorium. Gladys Horton and Katherine Anderson of the Marvelettes, sing on stage.

LEFT: Younger ladies within the viewers throughout a efficiency of the Otis Redding Present on the Montgomery Metropolis Auditorium. RIGHT: Gladys Horton and Katherine Anderson of the Marvelettes, sing on stage.

ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORY

“You’d go right into a city and also you’d discover any person good sufficient to repair a dinner for you and allow you to sleep in a mattress,” Rush stated. “You’d put some mattresses on the ground … otherwise you’d sleep in your automotive. That is what we had, man, and we did not suppose nothin’ about it.”

Potential hazard would come as artists handed between cities, Lauterbach stated.

Lauterbach interviewed round 25 individuals for his Chitlin’ Circuit e book. He heard tales that diverse from police discrimination to Ku Klux Klan run-ins.

“A lot of them have advised me about getting pulled over by police whereas they had been carrying all of their band gear,” Lauterbach stated, “The police would make them unload their tools and arrange and play by the aspect of the street to show they’re musicians and never working medication.”

He continued, “They’d be arrange on the aspect of the street performing whereas the cops are on the lookout for medication, which, after all, they did not discover. There have been these sorts of humiliations.”

The South would desegregate after years of marches, sit-ins and sacrifices by civil rights leaders, however echoes of the Circuit — identified now to some because the “Southern Soul Circuit” — stay current in communities at the moment.

City renewal plans within the 1960s and ’70s led to demolition of many landmark Black venues. People who survived, plus some new areas, host a rotating forged of artists preserving the blues, rock ‘n’ roll and soul music.

“Most individuals don’t name that the Chitlin’ Circuit,” Lewis stated, “however the social maintain of these venues is analogous.”

Comedy and theater nonetheless play on the Circuit, too.

Actor, author and producer Tyler Perry will be the most well-known up to date entertainer to chop his tooth on a 21st century city theater circuit.

“About this Chitlin’ Circuit, a variety of time we as African-American individuals have developed a lot that we glance down our nostril at sure issues,” Perry stated on “The Arsenio Corridor Present” in 2013. “What I discovered about this circuit, it was so great. … You had all these individuals who couldn’t carry out in white institutions in order that they went on the street in all these small juke joints with hen fries and chitlins and so they traveled the nation and they grew to become so well-known amongst their very own those who they had been in a position to assist themselves and and reside nicely.

In 2012, Lauren Karthyn, proper, dances on the Royal Peacock Membership on Auburn Avenue, as soon as patronized by celebrities akin to Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson and the place entertainers Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin and James Brown all carried out, in Atlanta. The Stax Museum of American Soul Music in Memphis.

LEFT: In 2012, Lauren Karthyn, proper, dances on the Royal Peacock Membership on Auburn Avenue, as soon as patronized by celebrities akin to Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson and the place entertainers Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin and James Brown all carried out, in Atlanta. RIGHT: The Stax Museum of American Soul Music in Memphis.

David Goldman/AP; THE COMMERCIAL APPEAL

“Lower to 1998 an I am doing the very same factor … touring round to African-American individuals. They’ve made me so well-known inside my very own tradition that I could not stroll down the road with out getting acknowledged.”

In the present day, a number of labels launch Southern soul data and a few radio stations spin the songs.

In the present day’s Circuit exists as a spot for artists akin to Rush or blues singer Benny Latimore to carry out for these with a starvation for the sounds of a long time previous.

“The viewers nonetheless wants the music,” Lauterbach stated. “They usually’re not getting the tales, artists and songs that they need from mainstream music.”

The post Inside the roaring nights that shaped American music appeared first on Correct Success.

source https://correctsuccess.com/finance/inside-the-roaring-nights-that-shaped-american-music/

No comments:

Post a Comment